On the panic that accompanies that which goes bump in the night…

People are scared to empty their minds

fearing that they will be engulfed by the void.

What they don’t realize is that their own mind is the void.

Huang Po

Not too long ago, when a lama came to the dharma center to teach on the Dujom Tersar cycle of chöd, I came across a few references in a variety of writings, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist that describe the experience of panic that arises in the face of the experience of loosening the intensity of the grasp around a permanent self. These reminders have been timely teachers as I have found myself recalling moments of ‘self’ destruction for lack of a better term, as well as deep listening to my own experience of periodic panic that sometimes presages a feeling of a less real sense of self. I feel that this is an under-explored topic, namely the fear that accompanies the spiritual path. Over the years I sometimes wonder if this fear is the fear that our practice will be (or is) successful.

Confess your hidden faults.

Approach what you find repulsive.

Help those you think you cannot help.

Anything you are attached to, give that.

Go to the places that scare you.

Machig Labdrön

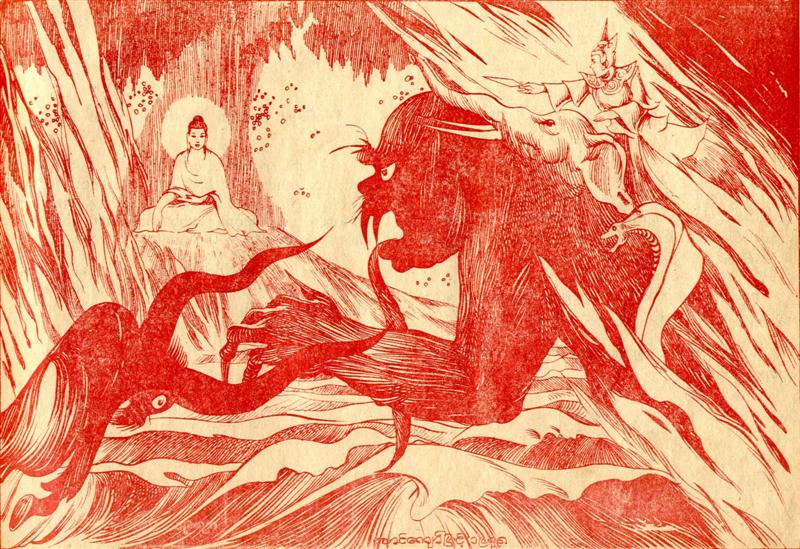

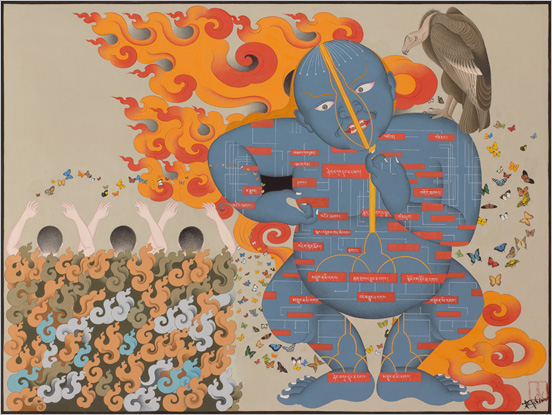

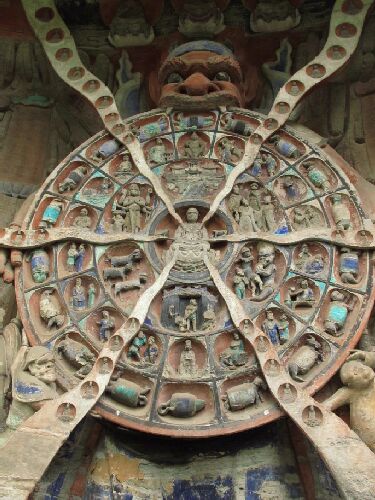

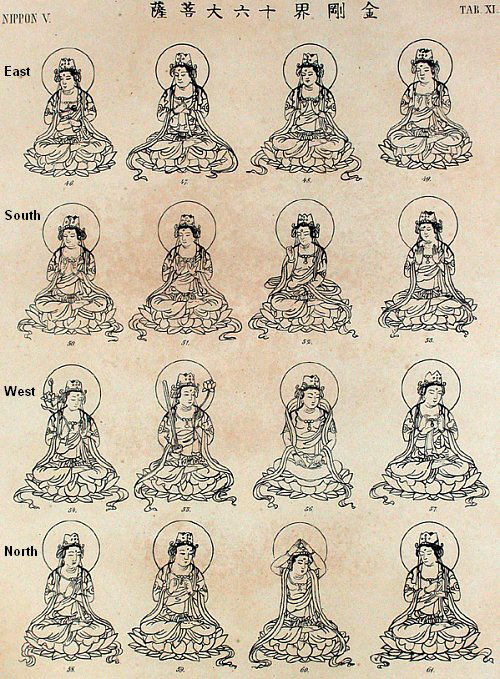

Within the context of the practice of vajrayana, the practice of chöd, regardless of any particular lineage, offers a very compelling way through which we might help effectively confront this self that tries to hold together the matrix of identity that wants to know and control the world around us. A complex alignment of dynamics, chöd offers a powerful visualization that chips away the plaque of identity, it slowly releases the grip of the hand that tries to maintain a handle upon what we experience. As we loose our grip, finger by finger, and we feel ourselves slipping, we are easily reminded of the truth of impermanence of the castles of sand that we create and imbue with such power and reality that before we know it, we and everything around us feels real, important, and vitally essential. Whether the visualization emphasizes Prajnaparamita, Vajravarahi or Tröma, it is essential to remember that they all represent the complete luminosity of emptiness; the vividness with which we do not exist, and the bliss associated with realizing that everything around us is pure appearance. The counter-intuitive act of visualizing oneself thrown into a kapala made up of one’s own skull and transformed into an ambrosial offering for all beings, or piled up as a mandala offering upon one’s own flayed skin, these confounding visualizations and the profound sense of generosity required tug at our sense of permanence and our desire to belong constellated in relation to a fixed point within time and space. It is not uncommon to feel a sense of resistance to the practice, a sense of tentative reluctance, or attempts towards pulling back within ourselves.

There can be a lot of pain and suffering when we become aware of how we cling to this wanting to “be”. This alone could easily be regarded as ‘going to a place that scares you’ that so much chöd literature seems to refer to. Sometimes this suffering manifests physically, with a visceral painful feeling, a hollowness or sharp sense of discomfort, other times it arises as a sudden busyness in which all of the sudden there is something very important that we find we need to do- something that distracts us from our practice. Sometimes these new things we find ourselves needing to do seem so important and vital that we are seduced by their wonderful meaning and uniqueness. These of course are the arising of demons. They find us wherever we are and rather powerfully unweave some of the fabric of confidence in resting in the view that allows for chöd to be the powerful practice that it is.

Ordinary people look to their surroundings, while followers of the Way look to Mind, but the true Dharma is to forget them both. The former is easy enough, the latter very difficult. Men are afraid to forget their minds, fearing to fall through the Void with nothing to stay their fall. They do not know that the Void is not really void, but the realm of the real Dharma. – Huang Po

The experience of groundlessness, I was once told by a psychotherapist who happened to be Buddhist, was not something to be cultivated, but rather, an experience more grounded and tangible was deemed as more valuable, within the process of spiritual growth. I have come across a number of psychoanalysts who warn in their writings that unguided exploration and or cultivation of the experience of groundlessness can lead to a state of psychosis. These warnings are interesting. They are interesting in part because I often wonder about the utility of combining psychoanalysis with Buddhist practice, especially if one is going to fully embrace emptiness of self. In all likelihood the combination of both Buddhism and psychotherapy can be a very effective way with which one can effect a necessary change in one’s experience of life to reduce suffering. Yet I sometimes wonder how much we benefit from aligning our living and breathing practice of dharma with the structures of our intellect such as modalities that seek to measure and define our experience as we move along our path as found within the psychoanalytic model. Our intellect often arises in a manner that does not make sense; especially when the sense of self is threatened. Like sparks, or flashes of lightening in the night sky, the reverberation of the reactive ego- the sense of self-nature wrapped up with the demons that keep it preoccupied- obey no one person. They are messy, sometimes terrifying and often very powerful. Similarly, the fast arrival of vajrayogini with her retinue of dakinis arise in an unpredictable way; this is why they are so integral within this practice and this too is why chöd confounds approaches that seek to find a restorative refinement and distillation of the Self. After all, how can one distill that which is not there?

Those who realize the nature of their mind knows

That the mind itself is wisdom-awareness,

And no longer make the mistake of searching for enlightenment from other sources.

In fact, enlightenment cannot be found by searching.

So contemplate your own mind.

This is the highest meditation one can practice;

This very mind is the perfect awakened nature,

the birth place of all the enlightened ones.

Jetsun Milarepa

What if we just stopped running? Stopped trying to make ourselves better, more qualified, more important, more knowable and “ourselves”? What if we stopped in our tracks and turned around to face the executioner of our ego-grasping and gave way to the fear that exists around that process? What if we let the associated pain and suffering come rather than defend ourselves and acclimatized ourselves to the gnashing teeth of the demons who come fast, or the methodical bone crushing of the demons who come slow? What if we stopped sublimating everything by actively using our minds to make everything seem like Dharma, and just rest so that things can simply arise as Dharma; ordinary and unaffected; unpatterned and free from artifice?

Perhaps this is the only way in which the strong grip of our fears and insecurities, our limitations and feelings of being unqualified, will burn off like a morning mist as the sun rises. Perhaps trusting in the process is part of this and putting down the willful need for change allows this sense of self- an illusory doer, be seen for what it is, an expression of empty luminosity.

On a more pastoral vajrayana and haughty lamas…

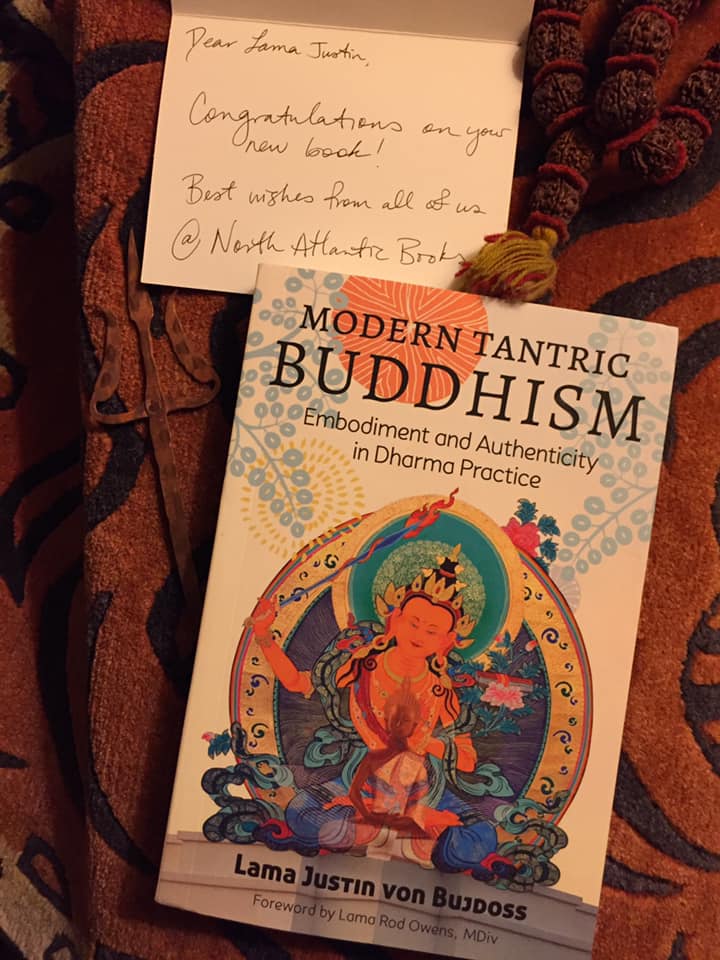

A few weeks ago I read an excellent article about Pope Francis shaking up the ecclesiastic leadership in the United States, and the subsequent reactions from more conservative Catholics. I found myself, despite my own sense of satisfaction in learning more about how the nuts and bolts of how Catholicism in America works, feeling sad and emotional around how far it seems that we as practitioners of Vajrayana have to go in the West before such conversations can occur around the quality of presence of our own spiritual leadership. In a way, we Vajrayana Buddhists are lacking when it comes to real authentic pastoral presence. When I say this I certainly don’t mean to imply that His Holiness Karmapa, or His Holiness Dalai Lama lack pastoral presence. They don’t. I have had the chance to be in their presence in very intimate settings and the degree to which they appear attuned to even the smallest concern of another person is astounding to witness. I refer to the lamas and administrators that represent our gompas, our Buddhist Associations, as well as the general dharma center leadership across the western world.

As it turns out, Pope Francis recently appointed Cardinal Donald Wuerl as the new head of the Congregation of Bishops, replacing Cardinal Raymond L. Burke for his conservatism and lack of pastoral affect. This change in leadership, while subtle in some respects, will hopefully produce long standing effects in how the church presents itself, to whom the church ministers and in what position it will take in relationship to the experience of the transcendent. Pastoralism is something that we commonly find within Christendom; in it’s most basic form it presents a spiritual concern centered around giving spiritual instruction and guidance to others. In this case, the parish priest who is intimately connected to the concerns and needs of his “flock”, needs spiritual, emotional and otherwise, comes to mind. Someone who works tirelessly for the benefit of others- in real terms, not just an aspiration to perform this task but to actually roll ones sleeves up, and get into the mucky mess that comes with being. Pastoralism also has applications that relate to music, art and philosophy, and a personal and ethical desire to return to the simple, the immediately real and what occurs naturally. As a hospice chaplain who operates from within the Vajrayana tradition as an ordained Repa, I am comfortable with discussions around the importance of pastoral presence and what that means. Yet I often find my Vajrayana contemporaries uncomfortable in challenging themselves in a way other than the way that tradition dictates. That the lineage of Tilo, Naro, Marpa and Mila has gotten so rigid and insecure is unfortunate.

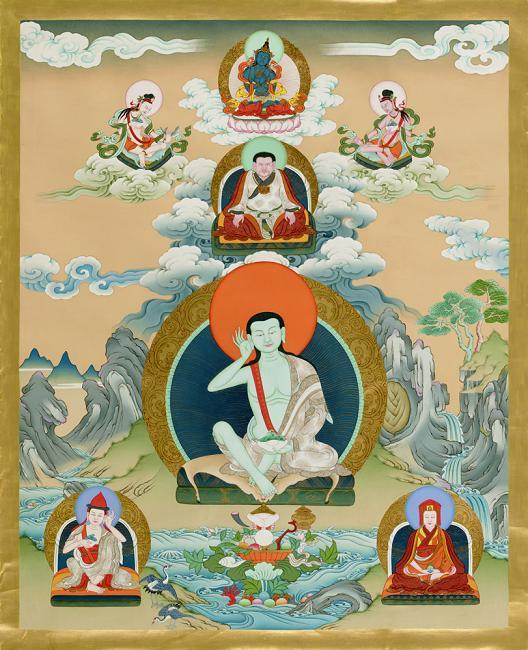

I think that one could definitely say that Milarepa had mastered a pastoral presence, or pastoral affect. In suggesting this I feel that it has less to do with the fact that he lived in retreat, in the pastoral wilds of Tibet as coincidence would have it, but that he could naturally -with simple immediate ease- sense the needs and suffering that others were consumed by because he could sit honestly with what arose within himself. This sounds easy to do, but in actuality it is quite painful and heartbreaking. It is difficult to see others stuck within their own experiences of themselves and even harder to see where we get stuck in similar ways. We generally don’t want to recognize how compelling the hallucinations that we have created actually are and how we lead ourselves around and around in circles, let alone try to work through the baseless obsession with the fact that we are imperfect and need to get somewhere before we can stand on our own two feet. Retreat is certainly a great way to develop spiritual insights, and it is very important, yet retreat does not necessarily produce compassion, and I am not so sure that it produces pastoral presence nearly as well and being fully engaged by what life brings our way. In fact I would argue the latter: compassion arises more uniformly, with more stability outside of a comfortable retreat setting. When living life in full one can easily get to the heart of difficult feelings that arise within the experience of pain and suffering, feel them and then let them flow into the next experience. Retreat can be helpful in this regard, however, I tend to feel that it is easier to seduce ourselves into a comfortable homeostasis in which we are never really forced to face our fears, never asked to consider the shadows, and never really asked to cut deep to the bone and feel that cold pain of the roots of our own suffering. This is why Milarepa is considered semi-wrathful within the text of his guru-yoga; the only way that he could go deeper and deeper within his practice is to cut with skill, precision and power. Cutting deep is important- it is hard and very uncomfortable. Yet, at the end of the day, we are best served when we can access the pain and suffering that we hide from. When we can do this pastoral presence is much more authentic. There is no better model for Vajrayana Buddhists than Milarepa if we are looking to foster a more pastoral Vajrayana.

Occasionally I fear that much of the way that the Vajrayana perspective is presented in the West is somewhat split between pedagogic models that either have students memorize terminology, acquaint oneself with logic, and years of study before they can say that we are Buddhists, and the other extreme that we can simply blend our curiosity of Buddhism with our practice of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, etc.- that we don’t need to worry about to committing to any one tradition. We are either definitely going to be born in one of the Hell Realms because we are terribly ignorant, or we are going to be just fine and we need not really worry about specifics- just show up say your prayers and do a bit of instruction without committing to a teacher or cogent path of practice. It is much easier to just follow the rules and sheepishly hide who we are in relationship to dharma than integrate the dharma into our experience of life.

We also seem to suffer from an overly Mahayana perspective around the long period of time through which we must practice before we become realized. We are very infrequently told (or shown) that liberation can come in this moment, on this very seat, in this very session. We are given a practice and generally told that it will take an incalculable (or at least an unknowable) amount of time before enlightenment occurs. We venerate past masters who were exemplary and also taught to believe that we are nothing in comparison to them- we are but just mere shadows. But is this really so? Why are we not taught to take greater responsibility for our realization? Why are we not taught to be creative in our practice, to take our seat and settle into our own pastoral authority? In fact, more often than not, the specific lineage that we are shown is presented more like a line which we shouldn’t deviate from, yet when one looks, most of the great masters struggled to challenge and confront such preconceived ways of being. Eveny lineage has masters who did whatever they needed to do to effect realization- if it meant breaking the rules, so be it.

I fear that some of the leaders that one finds within the mainstream presentation of Vajrayana lack the natural ease that Milarepa brought to the tradition at large: no monasteries, no particular school of thought to tether oneself to, no institutional affiliations, no orthodoxies, no expectations, no roles, just the experience of pure experience. Even though I say this, it should be noted that the growing interest by scholars in the development of the Milarepa’s hagiographical literature presents us with compelling evidence that the creation of the story of Milarepa morphed into what we know today from a wide variety of projections of what his life was thought to have been like by others centuries after his death. Even still, despite the fact that we may only be able to interact with our own inner Milarepa, and the true Milarepa may never be known, there is some indescribable inspiration that he evokes, not unlike the feeling of an early warm Spring day that leaves one feeling naturally resolved and content and excited for whatever comes next. For me part of the joy of Milarepa is that everything is okay, that within the experience of Mahamudra there is nothing to add, nothing to take away, nothing to do, and that we can rest in everything because it is all essentially one taste. This is a powerful root to a penetrating pastoral presence that is without fault. I try in my own way to allow this to inform me as a chaplain and as a teacher at the dharma center rather than whatever ‘rules’ or traditional norms may exist; whether this is a benefit and serves me well in either role is certainly up for debate. Lord knows, I am probably more of a hindrance than a benefit to anyone.

Instead many in the Vajrayana tradition here in the United States, especially those in positions of spiritual leadership seem to fall back upon textual dictates and scripture, the rules and maxims of form and function rather than engage directly, naturally, with how life, and thus, appearances arise. Spiritual bypassing, or the use of spirituality to disengage from actually experiencing what arises and resting within it, appears to be as much the western Buddhist’s unique disease as much as diabetes and obesity are the illnesses that currently define Americans. This bypassing appears to be caused by the constant retelling of the same old story that we are imperfect, that we are not enough and that we are somehow not whole in this moment. More than this, this type of undigested view lacks the rich fertility that provides us with the needed confidence, or escape velocity, to no longer be hindered by the gravity of our habits and misguided constructions of the universe around and within us. It is easier to build a fancy dharma center, easier to go into 3 year retreat, and easier to tell ourselves (and others) that we will never taste any of the fruit of the dharma as we are fundamentally obscured than it is to try to cut through our sad, sorry, slothful sense of being imperfect. There is no better way to blind oneself (and build up one’s sense of importance) than with dogma.

I am reminded of a story I was told about a group of western monastics who criticized a flower offering that a student at a dharma center made one morning. She had happened upon a field of wild flowers while during a morning walk and decided to pick a few to bring to the shrine as an offering. New to the dharma she was motivated by fresh devotion. By the following morning the offering was removed- I was told that the imperfections found upon the leaves of the flowers and the petals reflected the ignorance of the student. The group of monastics were quick to point out that all offerings have to be perfect, the very best- as this is what texts explain. Needless to say, I had a hard time hiding my mixture of disgust and sadness that the inner efforts of devotion made by someone new to the dharma was seen as a violation of protocol and a cause of negative karma due to ignorance. The unbending parochialism of this argument is a constant source of amusement for me. As a chaplain I often find myself having to operate from a place of creativity and skillful means to help provide others with a supportive environment even if it challenges the static spiritual dictates of a given person’s faith. Such rigidity would do more harm for a person who is dying than good.

I wonder what Pope Francis would say of the Catholic version of this event? What do we do when we become overly dogmatic at the expense of killing the experience of another? When do we let our religious dogma undermine our abilities to manifest the connection created by pastoral presence? What makes us Buddhist puritans?

How we work towards achieving this reconnection to our essential wholeness, our naturally expansive and vast experience of all that arises is ultimately up to us. This includes the specific techniques, degrees of effort, and the conceptual models that we temporarily use to get us to a place of spontaneous confidence and certainty. Most important however is that we don’t concertize the path, that we don’t rigidly hold onto our techniques (lest we become cold chauvinists regarding Buddhadharma), as well as a dialectical obsession with how much effort we must apply (we are tying to ease into the experience of Mahamudra, not train for a triathlon), or assign too much of an eternalist reality to the conceptual models we use (whether lay or ordained, male or female, well schooled or illiterate, whether we follow sutra or tantra, are logicians or ritual specialists or neither, we are working with the essence of mind; no one path is necessarily better than the other). Otherwise, the very vows that we take to benefit others become the very cause of perverse haughty dogmatism that does more harm than good. Before we know it we are no better than the demons that we thought we were feeding or coming to learn from and rather than spiritual friends become judges, applying dialectics gathered from scripture and commentarial literature rather than from the direct experience of mind. When does that shift occur? When do we go from spiritual friend to tormentor and judge? When does our fear prevent us from being with what arises and cause us to snuggle up within textual dictates to provide us with comfort and a defensive justification of laziness?

In a way, Pope Francis offers us a wonderful reflection of the ways in which we can become rigid and overly concerned with outer appearance. The conservatives in the church, those who apply the checks and balances of church dogma to the world around them as a way to orient themselves and assert meaning, often lack the same experience and sense of certainty than those who were parish priests and are familiar with the joys and sorrows of their congregations. This is obviously not unique to Catholics, in fact, this kind of separation feels much more prevalent in the Tibetan Buddhist world- and it also appears that we are too afraid to explore this lest we criticize the sangha (let alone cause a rift within it). It may be that ordained sangha and the large dharma organizations that we have created in the west are the biggest sacred cows that we as Buddhists need to confront.

In a podcast on Mahamudra that I happened upon by Reggie Ray, Ray artfully suggests that the lineage doesn’t care about us. Perhaps more to the point, he reinforces the point that our practice of dharma isn’t about our identities in relation to the lineage. The lineage doesn’t care if we become involved as teachers or administrators. The lineage doesn’t care about gompas or lack of gompas. It doesn’t care about dharma centers and their creation, maintenance and growth. The lineage doesn’t care about anything other than our work to recognize our natural face: enlightened being. Everything else is extra. Lineage doesn’t do anything other than reflect our essential nature. We do the rest. We create the world of systems, we collate texts, we publish books, we create limitations and neurotic obsessions, often in the name of lineage. If we are blessed with the chance to look back at our lineage and see how easy it is to get wrapped up in the peripheral details maybe we can return to the experience of simplicity: the experience of naked awareness. When we can do this we don’t have to become anything, or wear anything, or observe any vow, or follow any textual dictate, because we become, in that moment, the Dharma. There is nothing to add or take away from this basic reality.

A close friend who was recently trying to determine where she should be in late December and the beginning portion of January told me, “I could go to Bodh Gaya to participate in the Kagyu Monlam for “Dharma” or I could go home to be with my family and actually live Dharma”. Her time at home would be challenging and ordinary as time spent with family often is- in her case it would be more so as a relative had recently died and there was much support to be offered. The Kagyu Monlam, replete with lavish offerings, is a sophisticated mechanism for making aspiration prayers, a place to see and be seen as a Karma Kagyu practitioner, a place to go from lama to lama for blessings and teachings, and is in many ways the ultimate place to go for generating merit. Yet it is easy, it is obvious, somewhat predictable, and spiritually fattening; you can go there and haughtily throw your weight around feeling that you have unique karma and subtly build your ego. After all, look at me, I’m in Bodh Gaya at monlam, how fortunate am I? Going home to be with family, on the other hand, and all of the challenges that accompany providing support for the children and husband of the family member that recently passed away is a way to live all of what spiritual practice is about. It is also hard, confusing and sometimes boring and not very much fun.

I am grateful for my friend’s distinction here, it was timely and very well put. At the end of the day she answered the question for herself as to which one she decided to do. The question remains for us, which one would we prefer to and why? One is not necessarily better than the other, yet our decision says a lot about where we are right now and it is important to check-in and see where we are from time to time. Where are you?

On voices from the wilderness: “where we go from here…”

We recently lost two very important Kagyu Rinpoches, Karma Chagme, the head of the Nyedo Kagyu and direct lineal descendent of the great mahasiddha Rāga Asya , the very emanation of Amitabha himself, and Kyabje Choje Akong Rinpoche, a great social activist, dharma teacher. Along side Trungpa Rinpoche, Akong Rinpoche as one of the most important Kagyu Rinpoches in how he helped to plant the seeds of dharma in the West, but also create nurture Samye Ling and the system of Samye Dzongs throughout the UK, Scotland, Ireland, Europe and Africa. He was also vital in helping to local the young 17th Karmapa. As a lineage we have also recently lost Kyabje Traleg Rinpoche, Kyabje Tenga Rinpoche, and still feel the loss of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche.

As long as His Holiness the Gyalwang Karmapa is with us, no matter where he resides, I feel that we are in good hands, and as a student of His Eminence Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche, I feel that as long as his activities continue then the dharma will not only flourish but increase in concentration and power. May their lives be long and may they completely destroy our ego-clinging through the power of their skillful means! May their activities increase the depth and wisdom of the Kagyu lineage!

This said, there are some who express concern about where we as Karma Kagyu are going in the West, and I would like to throw my two cents into the ethereal debate. Rather than make this a global argument, metaphorically as well as actually, maybe we should just focus on the Kagyu in America. I do not presume to know much at all about this subject, and even more than that, I have no real qualifications to weigh-in on such a topic, but nevertheless, as one who has deep love for our lineage I am occasionally concerned about how we may be structuring ourselves here in the U.S.

As Karma Kagyu I feel that we can do more than we are doing. We obviously benefit from the hard work and extreme diligence and patience of the masters of the early era: the late Kalu Rinpoche, the late Trungpa Rinpoche, ven. Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, Thrangu Rinpoche, Bardor Tulku, Ponlop Rinpoche, Lama Norlha, Lama Lordro, Lama Tsingtsang, Lama Rinchen, Lama Dorje, and of course, their guide His Holiness the Gyalwang 16th Karmapa, Rangjung Rikpe Dorje. We owe them a debt of gratitude. Through these teachers we have the benefit of some very solid infrastructures for the study and practice of the dharma- we have a great number of translators, translation committees, places for extended as well as short retreat as well as the beginning of a sangha which while still young and tender might hopefully grow into a single unified family of victorious ones. Yet right now the sangha may be our weakest link.

America is a unique place in that across the board we like to think of ourselves on the collective level as a unified group that share similar values, and yet we also very easily cleave along a variety of lines that include ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, race and political views. The obvious benefit is that there is the potential for most anyone to find a niche within the American experience. The fundamental flaw is that we are only part of the group until we don’t want to be, until our desire-lines of identity pull us into our sub-groups. When we separate from the collective in this way, the American experience becomes very static and disjointed. Likewise, when we try to singularly drop our histories, the various layers of culture that have helped to shape us as people, in favor of the collective identity, we lose the richness and the brilliance that we bring to the entire American organism. There is something about the fundamental tension between the more idealized identity as Americans (which is a construction) and our identity as a member of a variety of sub-groups (also ultimately a construction) that allows us to question the values of both sides of our being that can allow us to grow into dynamic citizens. That said, there is nothing preventing us from remaining stagnant within our identity on either side, either a stalwart “American” or member of a sub-group that doesn’t want to be part of the collective . When this happens unity, connection and communication becomes impossible.

Similarly, the essential flaw that we as American Karma Kagyu face is the idea that we actually think that know what we are doing. We feel that we are correct in projecting a particular meta-view upon ourselves as followers of the wisdom lineage of the Karma Kagyu, and that this view has to be expressed in a particular unified way. We assume that we must all adhere to the values as a group that were most recently innovated by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye in 18th century Tibet, who while being an amazing genius and autodidact, has been used (perhaps unintentionally) to create a blanket meta-identity that may have been taken to the extreme. At times I feel that ultimately this lack of balance has led many who feel connected to a wide variety of sub-groups to feel left out and as a result, not integrated into the larger view of what we may be as a lineage. As if the notion of a unified Karma Kagyu lineage, or any lineage, has ever existed until the “modern” era.

I think that it is worth throwing into the mix that the lines of all four major schools of Tantric Buddhism might be more a product of modern academia than anything else. It might even be that we have all contaminated one another through the cross-pollination of inter-lineage growth in the past than our projections and assumptions allow us to believe. Our identities are more blended that we might like. An example of this can be demonstrated by His Holiness Sakya Trizin when he recently gave the empowerment of Dudjom Lingpa’s Three Wrathful Ones in New York City.

I think that it was Trungpa Rinpoche who called the Kagyu lineage the ‘mishap lineage’, which I will loosely interpret to mean that at its best our lineage just happens; it is not the product of strategic planning. Why is this? Well, perhaps we are not the product of controlled strategic planning either; our mind/heart matrix of thought/emotion is a system of constant mishaps, all sorts of stuff arises, sometimes we can clearly rest in what arises, other times we get carried away by our hallucinations. But one thing is certain, problems arise once we try to force a structure upon the way things should be.

In this way, I tend to wonder if we may have made the fundamental error of leaning too much upon the 18th/19th century classicism of monastic Karma Kagyu as a model for the entirety of American Karma Kagyu (the vast majority of whom are lay) in the 21st century. It sounds kind of absurd actually when I see it written out like that, and I don’t think that it is too much of a stretch to suggest that if this is the case, then perhaps we lose some of our credibility and accessibility with those who resonate with the sub-groups that feel at odds with the way the dharma is presented. How are young people with little interest in India or Tibet, let alone their history, and who have little money to travel to India to feel connected? What about some curious souls from the South Bronx, Brownsville, Oakland, Compton, or even large swathes of Suburbia who want to better understand their relationship to their experience of suffering to connect?

The dynamic energy of engaged being as is inherently expressed by a wide variety of groups of all imaginable ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, race and other points of orientation doesn’t seem to be held by the container of this kind of singular classical Tibetan approach. Perhaps it is paternalism or some type of chauvinism, and perhaps it isn’t- lord knows the internet is full of such debates, and my point here is not to cast blame upon anyone other than our limited view. That said, I tend to feel that what matters most here is that the essential tension between “self-identity” as a member of any particular group in relation to the experience of gaining certainty in our not having any particular “self” as taught through the dharma is being lost to an increasing number of Americans. These sparks of tension allow the power of tantric Buddhism to blow up our ideas of who we think we are and how we tend to conceive of the world around and within ourselves. To ‘inadvertently’ create the assumption that one can only experience this through assuming that we all need to be conversant in 18th/19th century Tibetan classical Buddhist thought only serves to disempower the vast majority of sentient beings in the United States. It allows few people to come and be held as they expolre the sparky nature of what it means to familiarize oneself with the view. Perhaps Europe is different, or Central and South America, and Aftrica, but I suspect not.

The way that much of the Karma Kagyu lineage is being presented these days in the United States appears to be more of a preservation of monasticism and the imposition of this structure upon the inner lives of the sangha, rather than a skilled blending, meeting people where the are, and creating the container that allows the safety and intimacy necessary to challenging the assumptions of who and what we are, and what the whole field of appearance might be.

The result is that it is not uncommon to find that there are many gorgeous Karma Kagyu dharma dharma centers, stunning in beauty and immaculate in appearance, real museum quality reproductions of what one might have found in Tibet before the Chinese holocaust. Yet, it is also possible to feel the cold clinical nature of many of these places. In looking even closer, it is easy to see how tender and fragmented the sanghas appear. This makes me feel sad. After all, it is sangha that is vital for the continuation of the practice of dharma. When I visit places that resemble these perfect visions of what dharma is supposed to look like visually, I think of Drukpa Kunley, Milarepa, Phadampa Sangye and Shabkar with great tenderness (and humor) and take delight in my meager identity as a so-called Repa. These teachers (myself completely excluded) were vital commentators, alternatives and voices in the wilderness that dharma cannot be owned, trapped in books, and is not only to be delivered through the medium of classicism which often runs the risk of becoming overly dusty and theoretical. There is a lot of wisdom in their path, and many teachings in their relationship with the institutions that presented dharma in a particular kind of way.

What we seem to fail to realize, or perhaps disassociate from, is that the Karma Kagyu lineage is best when it is a blended practice of fierce engaged practice activity mixed with the subtlety and discipline that one finds in Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye. Just as we need the sun and the moon for there to be balance on Earth, perhaps we need both the paths of Rechungpa and Gampopa as symbols of who we are, who we might wish to become, and from which point we wish to engage the dharma. We need to look at where we become too comfortable and lazy and bring our whole experience as people into our practice. Good dharma practice has nothing to do with beautiful dharma centers, rich coffers, and exquisite elegance. In fact, the best practice arises from confronting the entire hallucination of this “self” and the world around us. We are often well served to this end in challenging our assumptions of how our dharma centers should appear, notice when our devotion becomes the habit obsession rather than a mixture of connection and gratitude, and when in trying to be “good”, how we accidentally cause great harm to those we tell ourselves we are committed to benefiting.

Ultimately, everything that has been created by our foreparents within the Karma Kagyu in America is wonderful, and we should rejoice in the amazing progress. It really is amazing what has come into being. And yet, we might be getting a bit lazy and myopic and I pray that we can make things a bit more messy and sparky and dynamic for everyone who might be attracted to this vibrant and wonderful lineage. I pray that our dharma teachers can strike a rich and engaged balance for their students! I pray that our lineage can hold the experience of every person from every walk of life who approaches us! I pray that we face mishaps every day and that the sparks of tension within our experience of being cause endless dakas and dakinis to bless us!

on time machines, weaving words and loosening our belt so that our minds can expand…

My last blog post touched a lot of nerves- in a good way, from what I can tell, and it also seemed to have displeased others who came away from it thinking that it was written to complain about laziness, ‘spiritual materialism’ and the existence of a spiritual marketplace which often become more of a self-help, soft-core spiritual path. While I understand the reaction, I don’t agree with such facile readings of the post- not that its difficile in the first place.

Whatever the case may be, whether these posts, and this blog, are worth the ether that allow them a fragile existence of any kind or not, leads me to a few deeper problems that have been something of a point of concern as well as curiosity for me lately, that is: language and time.

I would first like to avoid the immediate association with these terms any cosmic relationship with philosophy and loosey-goosey bedroom-eyed mysticism, while simultaneously acknowledging that language and time are obviously thematically treated in great depth in both the study of philosophy and mysticism. It may be that we are best served (for the purposes of this post) in allowing our analytical minds, the mind of blended comparisons and of discernment, to step aside as we examine for ourselves within the context of the personal meditation experience, how and what language and time mean, and how they appear. Let’s put aside the study philosophy and try to approach this from what unfolds naturally on the meditation cushion, or, as we walk, or dream, as we paint and dance through this life of ours- for meditation experiences are always different from philosophical investigations.

We define ourselves through the use of language. Outwardly we describe who we are physically, our characteristics and so forth, and then we fill in all of the details, our personalities, likes and dislikes, and all the rest. We further dabble in collaborative fiction through supporting the personal narratives of our friends and loved ones, and in offering counter-narrative of those we dislike. Soon, what may have begun as a relatively blank page (a debatable point indeed) has become filled with a testimony of who we would like be, who we envision ourselves as, and the way that we interpret the world around us. This language is a tapestry of meaning, one in which we both consciously and unconsciously weave together a living history, along with the plotted trajectories of the future events that have yet to be lived. In and of themselves these products of our individual relationship with language are amazing works of art that capture how we conceive, what we can allow to be, and what we must keep at bay. They are our hells and our anchors; perhaps they prevent us from flying off into a manic subconscious world; or perhaps they confine us to knowable modalities of being that provide us with the tools for the experience of life. Whichever the case may be, and I suspect that it is most likely a combination of the two (and many others) at differing points in time, language -in this context- acts, more often than not, like a prison; it is like a thief, and even more, language is like an unreliable friend whom we continue to trust even though she will continue to disappoint. For somehow we cannot describe away the pain of loss, the experience of death, the terrible bouts with illness, and the fact that one day we will be forced to say goodbye to all that we hold dear- no matter how much we may try.

The images we create with our internal literary drives have a hieroglyphic quality in the true sense of the word hieroglyphic, that is: a highly symbolic form of writing which is difficult to interpret/assign meaning. In the beginning was the word. From that word, an entire world was created, a veritable cosmos- our interwoven personal narratives develop with increasing complexity and nuance creating a web, a net, or systemic literary story-line in which we capture every detail. As I sit here, writing both this blog post as well as my experience of today, the soft beautiful light coming through the windows between the treas and fluttering prayer flags is captured as is the sweet smell of a yet uneaten pineapple offered in a recent Mahakala tsok that simultaneously soothes and excites.

Everything we do, all we experience, tends to be added to this net of meaning that is cast upon the phenomenal world.

There are times when we are able to put down our pens, or turn off whatever device we use to compose these narratives of distinctive being- one of the most common device in such work is our discursive mind. The mind of spacial relationships, of color schemes, the mind of philosophy and dualistic comparisons. Perhaps this is also the sociology mind, the mind of architecture, the mind of economics, and the mind of urban planning. That part of us which organizes, the desire to play with the economics of mind; the way we become hypnotized by the production, consumption, and transfer of phenomena.

When we can put this down- although we’re not really putting anything down- then what we were formerly engaging with becomes less of an object and more of an experience. There is almost a sense of relief in this, a wonderful supporting ease and perhaps the experience of a type of contentment.

In his very condensed version of the Ninth Karmapa’s The Ocean of Meaning, entitled Opening the Door to Certainty, the late Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche touched upon the enhancement practices of Mahamudra meditation. These are described as ‘enhancement through eliminating five false ideas’. The first of the five false ideas is that of objects. Of eliminating the false ideas about objects Bokar Rinpoche writes:

Without grasping something real in the notion of samsara that must be abandoned and nirvana that must be actualized, but placing ourselves in the infinite one-taste of primordial awareness [of knowing] the non-duality of all phenomena gathered by pairs such as virtue and non-virtue, we eliminate false ideas about objects.

This is a wonderfully powerful instruction, that while presented as an enhancement practice in the context of the Mahamudra system, is worthy of examining, especially in light of how easily we craft global narratives of everything within and without. I wonder how we can ‘place ourselves in the infinite one-taste of primordial awareness’ or settle ourselves in a position of quiet knowing in which we can allow ourselves to dissolve the need for narrative, comparisons, and allow the direct of experience of the world around us (and within us) to arise; a dancing array of inherently perfect appearance. Easier said than done? I’m not so sure about that- if we can playfully try to fold this into our everyday activities, I suspect that bit by bit we can massage the habits of stale knowing. If we can play around with the view we’re really practicing something profound.

The second of the five false ideas is that of time. Of eliminating the false ideas about time, Bokar Rinpoche continues:

Although there is no fundamental truth about the reality of the three times, we think within a mode obscured by the division into three times. Consequently, realizing equanimity which does not establish a distinction of the three times, we eliminate the false ideas about time.

This instruction is especially relevant in helping to loosen the grasping of the compelling reality of our narration as we constantly pin things down (including ourselves) to various points in time. Our past informs us in the present and helps determine the future; or so we tend to think. Ideas of time having particular characteristics is a lovely subtle subject- Buddhism is rife with them: the number of aeons, life times, or years that it will take before we fully awaken is just one example. Assuming that the past was a particular way, the notion of the golden days of long ago in relation to these degenerate times, is another poignant example. The very notion of systematic evolution (individual spiritual evolution) is a wonderful blended assumption rooted in the false ideas of objects and time. How many others do we hold on to?

What other unexamined aspects of our faith tradition do we just assume out of the habits of appearance and time? What would it be like if we crafted our own notions based upon our experiences?

Wangchuk Dorje reminds us: “The division of the three times (past, present, and future) are simply the imputations of ignorant fools.” More specifically, he warns us that included within this is the relationship that we may feel that we have with the past and future. He further continues, “yogins and yoginis who have manifested this [realization] are able to bless a great aeon into an instant and an instant into a great aeon… …if they were separate entities this would not be possible.” Yet it is possible, and, it is up to us to ease into allowing this possibility. This gets back to having set ideas about who we are, what we are capable of, and all of the other stories we have woven.

What happens when we wrestle with the solidity of time? Or loosen our belts so that time can slip away…

When will your liberation occur? Forget the texts, and all of the things you have heard, when will it be possible to truly ease into the mind’s essential nature? After ngondro? After you have mastered your yidam practice? After a three year retreat? After ordination? After you die, in the bardo? After you die seven times? One hundred thousand times? In the future? What about right now? Did you already do it in the past, but got all distracted?

When we can see words as playful birds, and time reflected in the way that clouds appear and disappear in the sky, and the the solidity of our identities as the smoke of incense floating through the the rays of a setting sun, then maybe we can experience mind a little more clearly. Not just the mind’s stillness, but by feeling out, as if expanding awareness to meet the bounds of space, without saying, doing, thinking, making notations, and without being Buddhist. In trying to do this over and over, the artifice of relative reality can be seen, a necessary strange place that allows us to communicate, to help others, to support ourselves in the process of familiarizing ourselves with the mind- but not ourselves, not our identities. Yet when we tighten our belts, we become men and women, Buddhists, with mass, height, characteristics, distinct identities that feel, want and need. We have a cannon to follow and refer to, we experiment less and assume that it will all work out in the future, a bunch of now moments later, but the very now we live in is never seen as the free open experience of whatever arises without characteristics.

Wangchuk Dorje reminds us that we cannot realize this through “merely listening and reflecting, examining and analyzing, being very knowledgeable, having a sharp intellect, being skilled in exposition, being an excellent teacher or logician, and the like.” He goes on to quote the Gandavyuhasutra:

The teachings of the perfect Buddha are not realized by simply hearing them. For example, someone may be helplessly carried away by a river but still die of thirst. Not to meditate on the dharma is like that.

And:

Someone may stand at the cross roads and wish everyone prosperity, but they won’t receive any of it themselves. Not to meditate on the dharma is like that.

We can go around with ideas of this and that, with loads of empowerments, secret instructions and a plethora of practices to choose from but the real wisdom comes from practice, from trial and error. In fact, just one simple practice is more than enough- by sticking to it and blending it with our waking and sleeping moments great wonders are possible. We are very well served by examining how and why we hold these truths about ourselves, our paths, and time to be self-evident. In attempting to let the constancy of our personal narrative fall away like an unneeded belt, lets take these words and use them to unzip themselves so that our view is that of the experience of mind, fresh, free, naked and not of the three times.

On equivalencies and a new dharma center…

Lately I find myself reflecting on equivalence. Yet before I share my thoughts I would like to dedicate this blog post to Lizette, a hospice resident that I had visited who died yesterday. May her experience of the bardo be one of restful ease!

As a chaplain the notion of the possibility of equivalence helps to bridge the differences between myself and others- between what might be expressed, or needed, by someone other than myself. Ascertaining equivalence, a necessary act of juggling, forces us to examine our orthodoxies. It opens the door to the barn where we keep all of our sacred cows, our assumptions, and very often, all of the ways that we lazily forego really examining how we are with others, especially in relation to our larger belief systems, and all of the other spheres that we occupy. When I can find the points of connection that I share with people with whom one would assume there is no connection, I am usually left with an understanding of just how similar I am to others. Equivalence helps to reduce the promotion associated with self-elevation might make me say, “As a Buddhist, I am different from you in that I believe….”, or, “As a Vajrayana Buddhist I feel that my path is better because….”

The word equivalence has its root in the early 15th century middle French word equivalent, which is a conjunction of the prefix equi meaning equal, and valent (as in valence) and valiant, which at that time period referred to strength, bond, and a “combined power of an element“. I am reminded of the importance of valence electrons in chemistry and physics- specifically how the balance of electrical charges between atoms necessitate a sharing of electrons thus creating bonds between atoms. From these bonds everything around us arises; indeed, through the play of interdependence everything that we know can come into being.

I find this metaphor helpful as it involves stepping out of the traditional norms of Buddhist language. Of course, one might ask, “what language isn’t Buddhist?” In this question is a profound point. If our approach to Buddhist practice, whatever form that may take, or for example my chaplaincy informed by my practice of Buddhism, cannot interpenetrate other forms of language, other modalities of thought, or other creative models, it lacks the ability to maintain equivalency. In this manner it ends up lacking the ability to be itself while remaining fluid; it remains separated and isolated, at odds with whatever other it may encounter. In this way I know that I run the risk of falling into a discursive self vs. other perspective when I feel a lack of openness, fluidity, and ability to be at ease with whatever arises.

It can be easy to feel self-conscious within, and around, our belief system which if one is Buddhist, often undermines our very ability to be Buddhist. Indeed sometimes we try to be “Buddhist” as a way to distinguish oneself from others. This kind of separation is a terrible violence- an awful form of self-inflation and spiritual self-destruction that seems to miss the larger point.

And yet, if we explore the possibility that no language can be found that exists outside of the framework of Buddhism in its pure natural manner of expressing itself then it is easy to appreciate true natural arising equivalencies. We are no longer “Buddhist”, we just are, which I suspect was what Shakyamuni came to value within his spiritual quest.

Over the past two weeks I have had the fortune to visit two women who were actively dying at two different hospices in the New York City area. Two very different women, going through different experiences of similar processes: dying. Both of these women had strong spiritual paths- unique paths of self-taught wisdom borne through the constancy of the repeated trials and tribulations that only a full life can bring. In their own ways, as self-taught “outsiders” they were Christ-like, and Buddhistic, and spoke of pure a basic expansive being without necessarily referencing any particular Buddhist vocabulary. Indeed it appeared that the slow fading of the flickering flame of their life allowed them to rest in a peaceful alert awareness that was a real joy to experience. Here I was, a chaplain, asked to come visit these two women who in that moment expressed a depth of view that I could do nothing but rejoice in and admire. I left feeling very confident in their process- they were touching a nearly inexpressible beauty. The visits with both women were punctuated by long silences with much eye contact- with simply being together, with a basic human connection.

Language, with its structural intricacies, its variegated forms, and kaleidoscopic ability to transform, often acts as a buttress in relation to our habitual referential reactions. It allows for, and instills, comparison -creating an endless system of distinctions. A literary color wheel, language runs the risk of pinning everything around us down; leaving us with a sense of knowing. And yet I wonder, where and when, does knowing intersect with being- with the quiet awareness from just being? What is the nature of their relationship within us?

My experience with Lizette, one of the two hospice patients described above, was that whenever I tried to use language and vocabulary to capture what she told me that she was experiencing a clumsy formalism ensued. The beauty and power of her experience of being was made overly solid, overly distinct and “other” by trying to define it. The only thing that kept this feeling alive was to join with it; to sit with her; and to not “know” it, but to be it.

What is the difference between discerned knowledge and knowing borne from resting within the moment? Where, or perhaps more importantly, when, do our assumptions, our knowledge, or our better sense and logical mind of discernment (a deep and satisfying place of self-importance) get in the way of simple being? How does language and knowing try to contain the simple being that is needed to allow us to rest in all of the equivalencies around us?

I am currently working on establishing a Dharma center here in Brooklyn called New York Tsurphu Goshir Dharma Center. This center is the only center of His Eminence the 12th Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche, Regent of the Kamtsang Kagyu Lineage. Just yesterday we received our 501 c 3 status as a church! It is a great honor and joy to co-Found and Co-Direct a Dharma center headed by a mahasiddha, and amidst all of the uncertainty and fears of failure, or that this will be a complete disaster, I keep coming back to memories of ngondro and the trials that Milarepa, our not so distant father, underwent.

Rob Preece, in his book Preparing for Tantra: Creating the Psychological Ground for Practice, offers a compelling argument for equivalency as it arises between aspects of the hardship and challenge created by undergoing ngondro and other hardships that may share a contextual similarity. Preece describes how all of the work and hard physical labor that he put into helping to build a center that Lama Yeshe was establishing was a prime ground for focusing the mind around dharma practice, planting aspirational seeds that would doubtlessly blossom into mature trees that provide support, shelter and benefit for others. Indeed, I know that as I challenged my body by carrying hundreds of pounds of building materials, the back pain and discomfort of refinishing the floors in 100 degree heat lead me to feel closer to Milarepa than I have felt in a long time. The practice of demolishing old structures, hanging sheetrock and cutting my hands while rewiring the shrine room allowed me to appreciate Preece’s point that ngondro was a creation meant to challenge, to purify, and to create gravity around dharma practice. My seemingly small daily endeavors, in reality, connect me to my spiritual lineage which allows me to feel close to Naropa, Marpa and Milarepa.

Ngondro is one thing- a practice that I value and feel is too often treated as just a preliminary that is to be rushed through, but how is chaplaincy different? Can it be any different? When we really look, can there even ever be a difference?

Milarepa never did ngondro, nor did Naropa- they had the benefit of having their teachers skillfully put them in difficult circumstances. At first glance it could be thought that it’s just hardship and difficulty that is implicit in these kinds of challenges; but when you look a little closer, it looks more like what is happening in through these experiences is that the view is being clarified.

What is being clarified, or purified? How is it really purified? These questions are both rhetorical and actual and beg to be asked. Blindly following through a ngondro pecha may be better than killing insects, but perhaps only in that it plants seeds that one day one may actually practice ngondro. And when we actually practice ngondro, where is there anything that exists outside of that practice? Refuge is everywhere. The experience of Vajrasattva’s non-dual purity of unmodulated mind is everywhere. The accumulation of merit arises with every breath. The lama is everywhere. Yet when we don’t “practice” ngondro what happens to refuge, the essence of purity, the accumulation of merit, and the blessings of the lama and the lineage?

I feel that there is a lot of wisdom in being able to rest into the awareness that accompanies being. It acts as a reset button of sorts that allows us the ability to see things more clearly, to appreciate the richness of whatever arises without creating conflict, and to meet others where they are without needing to change them. In this way, and with this perspective as a motivational factor, the world around us has infinite potential as a ground for practice. New York Tsurphu Goshir Dharma Center becomes as meaningful as Bodh Gaya in India, Tsari in Tibet, and yet is no different from sitting on the subway of being surrounded by the overwhelming bustle of Times Square, as everywhere can be the center of the mandala of the experience of reality as it is. It’s impossible for everywhere and everything to no longer function as the ground for practice.

This is the wish-fulfilling jewel quality that can be associated with resting in being with all of the equivalencies that surround us. This is an expression of the multi-valent interconnected relationships that imbue our experience of reality with all of the qualities associated with pure appearance as described in dzogchen, mahamudra, the pure view or sacred outlook associated with yidam practice, and quite possibly the experience of grace in Christianity, or wadhat al-wujud, the unity-of-being as described by Sufi master Ibn ‘al Arabi.

So whether you are helping to renovate a place of dhrama practice, or simply liking it on Facebook, or enduring trials similar to those of Naropa, Marpa and Milarepa, or laying in a hospice bed in Queens, New York, who is to draw distinction between the type of, or depth of experience that we undergo?

Can we quiet our mind of endless comparisons? Or allow for the mind of analytic distinctions to settle itself?

In doing so, perhaps the simplicity of being that arises reveals a constant soft rain of blessings and opportunities for authentic clear being. May all beings taste this ambrosial nectar expressed by the blissful knowing glance of all of the mahasiddhas of all traditions in all world systems. Gewo!

On resting with Tilopa…

Recently I have found myself returning to some of the amazingly pithy meditation instructions attributed to Sri Tilopa (988-1069), the well-known Indian Buddhist mahasiddha who was the forefather of the Kagyu lineage. His short, often poetic instructions, are something that help me in my personal meditation practice, as a ground for keeping myself feeling dynamic and internally connected as a chaplain, and in explaining to others the vajrayana perspective regarding what arises within the approach to death. An example of such an instruction is as follows:

If you sit, sit in the middle of the sky.

If you sleep, sleep on the point of a spear.

If you look, look upon the center of the sun.

I Tilopa, who saw the ultimate, am the one who is free of all effort.

The expansive clarity of this type of instruction, for me at least, is very resonant- it offers a way to feel my experience of mind blend into the wideness of space while also experiencing a sense of focus; a relaxed single-pointed experience of breath, sound, transparency of thoughts, and edgelessness. When this experience arises I feel very connected with Tilopa, as well as the other Indian mahasiddhas Naropa and Maitrepa. Sometimes however, I feel that I need a more graded approach to this experience of mind. When this occurs, I tend to lean on Jey Gampopa for support.

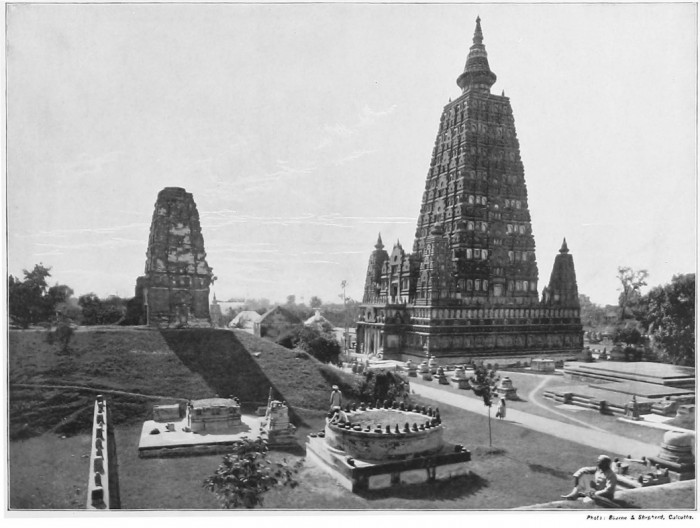

More specifically, I rely upon Gey Gampopa’s Precious Garland of the Supreme Path, and even more specifically I come back to the 5th chapter of this wonderful text: The ten things that you should not abandon. I had the wonderful fortune of receiving instruction on this text by the Venerable Khenpo Lodro Donyo, abbot of Bokar Ngedhon Chokhor Ling, in Bodh Gaya in the fall of 1998. This was during one of the many Mahamudra seminars that the late Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche held- truly magical times when we could all sit together under the bodhi tree to recite the 3rd Karmapa’s Mahamudra Aspiration Prayer, spend time in meditation- simultaneously touching our original nature- as well as physically touching the ground that supported the practice of all of the generations of Buddhists who had come before us in Bodh Gaya back all the way to Shakyamuni himself.

It was in that environment, and within that emotional frame of mind, that I came to learn of the ten things that one should not abandon. These ten things are: compassion, appearances, thought, mental afflictions, desirable objects, sickness (suffering and pain), enemies or those who obstruct our practice, methodical step-by-step progress, dharma practices involving physical movement, and the intention to benefit others. Gampopa’s list is very sensible, it is noble in the sense that it seems to be endorsed by Santideva himself; it is imbued with a heartfelt concern for the welfare of others as well as a methodical presentation of the training to see that appearances- be they attractive or not- are just mere appearance. The misapprehension of appearance, or appearance as taken as an independent entity separate from ourselves, is the very cause of our experience of suffering. As with all great dharma texts, it is heartening to see how just one small portion, in this case the 5th chapter of a 28 chapter text can offer the entire path to realizing one’s essential nature.

In looking back at the notebook that I have from the session when Khenpo Rinpoche taught this chapter, I can return to my exuberance not only for this chapter as a whole, but for Gampopa’s explanation of how one should approach the non-abandonment of mental afflictions. As a chaplain, when I am in the hospital, I very rarely meet people who desire to not abandon their experience of suffering: their fear, their psychic pain, their feelings of abandonment, of futility, of anger, or attachment to family- let alone attachment to ideas of how their life should or shouldn’t unfold. This experience isn’t unique to the hospital either- I and most of the people who I know spend a great deal of time fighting with these emotions. Perhaps this is why they are called mental afflictions.

Anger, attachment, pride, jealousy, ignorance. When we really sit quietly with these words they are not just words- they are worlds; worlds of suffering, worlds of feeling like we are right and others are wrong, that we don’t receive the credit or accolades that we deserve, that if only I had this, or was a that, then things would be the way that they should be. On and on and on…

Gampopa advises us to try three modalities with regard to facing and not abandoning our mental afflictions. We can avoid them- that is, avoid whatever causal conditions that might make them arise. We can transform them- or try to transform what these emotions unlock within us. Or finally, we can rest in them as they arise. Whichever modality we tend towards, there are two things to remain mindful of; how we habitually fall into one of these three modalities, and the degree to which we can honestly assess our relationship to that which we struggle with. Each of these ways of facing and not abandoning our mental afflictions can be techniques of liberation or techniques of seductive self-enslavement.

The process of avoidance is a very grounded, stable and well-meaning way of not abandoning our mental afflictions. It honors the way they arise- it honors their root- without forcing us to become affected. This way of approaching difficulties, painful habits, and stubborn aspects of our identities allows us some distance from the “heat” of the moment that comes with embodying our reaction to our mental afflictions. One could even go so far as to say that this modality is somewhat analytical in approach, it is disciplined and measured. The shadow aspect of avoidance is not acknowledging the mental afflictions that bring us pain and suffering. Not much good happens from simply ignoring things, or not letting aspects of ourselves have the light and air that they need to grow. Right now, the shadow of this modality comes to mind in the form of the image of a neglectful parent who doesn’t want to see who their children really are.

Transformation is a common methodology that one finds in the various levels of tantras. It involves playing with the way that we perceive our mental afflictions. This type of restated relationship allows us to meet head on those feelings that would normally make us want to run away. In this way the dross becomes pure; the dirty is seen as clean; and that which torments us achieves the possibility of bringing meaning and peace. True lighthearted transformation- transformation with ease- is hard to effect. Transformation has a terrible shadow side that involves the desire to fix; or more bluntly an inability to meet things as they appear without making them into something positive. As a chaplain, I witness many people struggle with maintaining a relationship with difficulty and pain, uncertainty and loss, and sickness and death without trying to “fix it”. The constancy of a “make-it-better-plan” can be exhausting and create untold suffering. It feels profoundly important to examine how this modality of maintaining a relationship with our matrix of painful emotions can relate to a desire to not allow honesty around what we are feeling and from where the roots of these emotions arise. (Here is a link to the related shadow of spiritually bypassing.)

Resting in whatever arises, the third modality presented by Gampopa, and the favorite of Khenpo Lodro Donyo while he was teaching, is an instruction that one commonly finds within the Kagyu and Nyingma traditions. It is profound- and it also very difficult to do honestly. As we saw earlier, anger, attachment, pride, jealousy and ignorance are powerful. To rest within rage for example- to feel one’s pulse quicken, and heart beat heavier and louder, while one becomes physically tight and flushed, as the explosive heat of anger and impatience engulfs us- is not a particularly comfortable feeling. (For a look at some of the difficulties involved with taking on these fierce emotions, you can read a previous post on Mahakala here.) Then there is the “resting” part. This term gets thrown around very often that I wonder if it doesn’t end up having a multitude of meanings nowadays. I know that I have met Buddhists of other traditions that take the term literally and assume that it is akin to taking a nap or “resting”.

Resting actually refers to maintaining a focused (often described as ‘single-pointed’) awareness of appearance as it arises in the moment. In this way, Tilopa’s instruction from the beginning of this post seems a wonderful way through which we can re-engage the term resting. One quality of resting is being at ease. In this sense when Tilopa refers to three different ways of being- siting, sleeping, and looking- he is referring to three ways that we can rest in what arises. We can do it formally, as in sitting practice. We can do it within the experience of sleep, mind appearances arise when we sleep just as when we are awake. Finally, in looking, perhaps a passive “every day” experience as well.

If you sit, sit in the middle of the sky.

Where is the middle of the sky? The true middle? Where are its edges? Where does the sky end and something else take over? As we sit and remain resting with a sense of ease can we feel the expansive qualities of our minds? Where is the edge of our mind? What does a thought look like? Does it have a source that you can identify? Where do thoughts go when they are no longer so magnetic?

If you sleep, sleep on the point of a spear.

When our thoughts feel sticky and magnetic, when it is hard to not feel drawn into them and let our inner film projector play, what happens when we remain concentrated? What does that “single-pointed” awareness feel like? When we can feel and notice our breath; when we can maintain focused awareness on the way the inner film projector plays; on how a particular thought will hold us within our inner gaze, what do we notice about our experience?

If you look, look upon the center of the sun.

When this focus can be maintained as we look out at the world as it goes by around us, where is the sense of stillness? From where does that arise? What happens to the way that you notice the way that things arise while maintaining a focused awareness upon the expansive quality of our minds? Is there ever not enough room for what arises within our field of reference?

I Tilopa, who saw the ultimate, am the one who is free of all effort.

What if removing all effort was all that you had to do? What would it be like to maintain that within your experience of life?

Instructions such as the ones that Tilopa left behind for us are rare and powerful. It has been roughly one thousand years since Tilopa passed away, and yet through these four lines it is amazing how much of a connection we can feel with him. Five generations after Tilopa, Gampopa further crystalized the importance of being someone who “is free of all effort”. And while there are may pitfalls around how we may feel that we are directly engaging what arises within the moment, there is much beauty in the journey. Perhaps, slowly moving through life, through the wonderous field of appearance, we can increase our sense of ease and relax into an experience of effortlessness. What an amazing thing to aspire towards.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)